A Lie of the Mind

“The mythology has to come out of real life, not the other way around. Mythology wasn’t some trick someone invented to move us. It came out of the guts of man.”

—Sam Shepard, 1985

Playwright Sam Shepard’s biographical sketch:

The Sam Shepard Papers in the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University provide a comprehensive biographical sketch:

Sam Shepard: Stalking Himself (1998)

Produced by PBS Great Performances, “Sam Shepard: Stalking Himself” is accessible via Internet Archive:

Highlights:

“[Tooth of Crime] is more about an image, this thing of being seduced into believing one is what you make yourself to believe you are.”

“I mean, I’ve known Americans who have gone over to Europe and have become European, but I don’t think I could ever do that. I just belong here. I mean, made me understand the nature of being tied to a culture that you can’t get away from, can’t get out of it.”

“It suddenly occurred to me that I was maybe avoiding a territory that I needed to investigate, which is the family. And I avoided it for quite a while because to me, it was a danger in… I was a little afraid of it, particularly around my old man and all that emotional territory. I didn’t really wanna tiptoe in there and then I thought, well maybe I better. So I guess it’s sort of a curse.”

“I grew up in this World War II world where the women were continually trying to heal up the men, you know, and suffering horribly behind it. Now, I don’t know why that came about but I have a strong feeling it had to do with World War II. That these men returned from this heroic victory of one kind or another and entered this Eisenhower age and were devastated in some basic way, you know. I mean, all those men that were of my father’s generation seemed like they were devastated in a way that’s mysterious still.”

From Cruising Paradise:

“1943. The Office of War Mobilization was invented. My dad is dropping bombs on Italy. I’m born, without a clue.

1943. There’s a little motor court on the outskirts of Mountain Home, Idaho. Through some secret code system my father’s worked out in postcards with my mother, she deciphers the exact room number and time to meet him. No bomber pilot is supposed to reveal his itinerary to even the closest blood relative.

1943. “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To.” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore.” “Comin’ In On a Wing and a Prayer.”

1943. My father is having a nightmare on one of the twin beds in the bungalow of the motor court in Mountain Home, Idaho. I’m sleeping in the bottom drawer of the dresser that’s been pulled out on a throw rug. My mother is quietly taking a shower. My father is seeing bombs raining on Italy. He sees the hand-painted cartoon faces on these bombs falling away. He sees his own white hand stretching out of the cockpit window, desperately clutching, trying to catch these painted monster cartoon creatures before they smash the blank face of Italy.

1943. “God is my Co-Pilot” hits the bestseller list. I’m born. Without a clue.”

“There was a trauma that was mysterious. And the women didn’t understand it, and the men didn’t understand it. So the medicine was booze. For the most part, booze.”

“I do honor the ones that have come before me, you know. It’s ridiculous to think that you were born out of thin air. There’s ancestors. And if you don’t honor your ancestors in the real sense, you’re committing a kind of suicide, you know.”

Shepard’s father was a first lieutenant B-24 “Liberator” pilot in WWII

“Plastic model airplanes covered in dust and cobwebs of World War Two fighters and bombers hang from the ceiling directly above the bed” (Shepard, A Lie of the Mind 31).

Shepard’s Connective Dramaturgy

From “Under the Influence: Alcoholic Families in the Plays of Sam Shepard, 1977-1985” by Jackie Norby Czerepinski:

“At many levels, A Lie of the Mind reprises subjects, characters, relationships, actions, and images from the earlier family plays. Jake and Frankie echo the Hero brother/Scapegoat brother dichotomy of True West. Jake's bedroom is Wesley's bedroom from Curse of the Starving Class, the ceiling festooned with model planes in honor of the flyer father, the alcoholic whose drink is ‘Tiger Rose.’ Bar—hopping near the Mexican border with their respective offspring, Lee and Austin's father lost his teeth; Jake and Sally's father lost his life. Lorraine's account of pursuing her husband cross-country expands on May's tale of her mother's pursuing The Old Man in Fool for Love. The pact of secrecy in Buried Child and the brother—sister pact in Fool for Love become the pact between Frankie and Sally that protects the secret of their father's death. Meg shares with True West's Mom and Ella in Curse a paradoxical concern for order in the house; violence is tolerated or overlooked, but no one may shout. Helpless Baylor and crippled Frankie replicate the tug—of—war over the blanket that Dodge and Bradley have in Buried Child. Characters frequently confuse their own, and others', identities and some seek, through performance, an authentic self. These and many other echoes of the earlier family plays in A Lie of the Mind create a unified background against which the progression of Shepard's attitudes, particularly toward gender and the inescapability of family engendered fate in an alcoholic family system, becomes clear.

“As in the preceding family plays, Shepard draws on his experience of family: the consequences of Beth's brain damage resemble the condition of Shepard’s mother-in-law, Scarlett Johnson Dark, who recuperated in his home following a cerebral hemorrhage and brain surgery in 1979; Jake's father is Shepard's father whose death is explored in Lie as his life was in the earlier plays. The new directions pointed to in the play reflect a new determination in Shepard's own family expressed by his sister Roxanne: ‘What happened is we decided to try to put this family back together’ (Freedman 20).

“Despite the changes in authorial point of view detailed below, neither critics nor playwright appear aware of the primacy of Samuel Shepard Rogers II’s alcoholism. Immediately before the opening of Lie, Shepard spoke of his father's consuming rage:

‘When you're younger, that rage is completely misunderstood. It seems personal when you're a kid. This rage has to do with you somehow. Then as you get older you see that it had nothing whatever to do with you. It had to do with a condition this man had to carry because of the circumstances of his life, those being World War l, the Depression, the poverty of the Midwest farm family. And all these things contributed to this kind of malaise.’ (Freedman 20)

…

“In A Lie of the Mind, from the perspective of the systems view of the alcoholic family, Shepard and his characters, particularly the women, confront the destructiveness of their family systems and by exposing familial delusions are able to move beyond the tyranny of dysfunctional rules and roles. More pointedly than in any of the other family plays, Shepard questions the inevitability of succumbing to family determined fate.

…

“In several respects, A Lie of the Mind signals Shepard's reappraisal of the conditions of family life and there are significant changes in the way he regards alcoholics and alcoholism. Shepard’s treatment of alcoholic fathers and sons in A Lie of the Mind differs significantly from the portraits of drinkers in the earlier family plays. Jake is alternately pitiful and frightening. He lacks Tilden's childlike charm and the humor of Eddie, Lee, and Austin: alcohol stimulates no painfully amusing antics, no moments of tenderness.

…

“Shepard treats the act of drinking as differently in Lie as he treats the alcoholics. Sharing drinks brings death rather than connection; it stimulates no pleasant memories, creates no camaraderie.

…

“Shepard's attitude toward the violence engendered by alcoholic families changes in A Lie of the Mind as well; violence takes on a different character than it has in the other plays. In the previous family plays, the specifically human damage violence does either emerges indirectly, is negligible, or is kept offstage: Weston's family fears him, for example, but we do not see him physically hurt them; neither Austin's attack on Loe nor May's on Eddie does any lasting damage to their brothers; Emma's death in the explosion of the car is implied rather than shown. We see or hear objects rather than people smashed: the door in Curse of the Starving Class, the bottles and the screen in Buried Child, the typewriter in True West, Eddie's truck in Fool for Love. Beth's condition in Lie is Shepard's most vivid depiction of the human cost of violence. The beating that Jake believes killed Beth is clearly not the first he's given her; Jake, Frankie, Sally, and Beth all refer to earlier beatings. Beth confronts us with undeniable evidence that violence hurts, that it does irreparable harm. Further, Shepard locates the reason for Jake's explosion emphatically within himself rather than providing justification or provocation outside the character.

…

“Exposing the lies of the mind sets several characters free in the play. Like May in Fool for Love, all of the women in Lie repudiate to some degree familial denial and delusion. The consequences of truth-telling, however, are more profound and more hopeful in the later play for both families.

…

“Lorraine asks the key question of the play: ‘Is there any good reason in this Christless world why men leave women?’(81). Jake's answer is Shepard's answer: ‘These things—in my head—lie to me’ (120). The lies of the mind, rooted in the culture and exacerbated by the multigenerational patterns of the dysfunctional family, victimize both men and women. Facing the truth, and telling the truth, may be painful, but it liberates. For the first time in the family plays, Shepard allows his characters to elude the determinism of the alcoholic family.”

Reference Glossary

“BAYLOR: Bunch a’ Oakies.” pg. 26

Oakies refers to people from Oklahoma, but it became a derogatory term in the 1930s referring to people from the Great Planes who migrated to California during the Great Depression.

“LORRAINE: You got everybody buffaloed, don’t ya’?” pg. 30

Buffaloed means intimidated or baffled.

“MIKE: Well, there’s only one day left in the season and he hasn’t got his buck yet.” pg. 39

In 2024, Montana deer and elk hunting season ends on December 1st.

“LORRAINE: You can bet yer bivey on that.” pg. 64

A waterproof bag used for camping.

“LORRAINE: Pictures of Bing Crosby and Ginger Rogers and Ida Lupino and Gene Autry and Louis Armstrong.” pg. 67

Bing Crosby: Singer and actor

Ginger Rogers: Actress and dancer

Ida Lupino: Actress and director

Gene Autry: Actor and musician

Louis Armstrong: Trumpeter and singer

“BAYLOR: You look like a roadhouse chippie.” pg. 82

A prostitute.

“LORRAINE: That was my sorrel mare.” pg. 85

A red horse with light hair.

“LORRAINE: I found it! Here it is. Right here. Sligo-County Connaught.” pg. 86

Sligo is a county in the province of Connaught (here, in dark green).

“BAYLOR: They haven’t changed it, have they? Maybe added a star or two but otherwise it’s exactly the same.” pg. 90

Alaska and Hawaii were the last states added to the U.S. in 1959.

“Dedicated to the memory of L.P.” pg. 4

This dedication refers to Lord Pentland (Henry John Sinclair). Pentland, a British businessman, founded the Gurdjieff Foundation of California. G.I. Gurdjieff was a philosopher and spiritual leader whose ideas influenced a number of artists, including director Peter Brook.

“BAYLOR: All they got is that Eddie Jackrabbit. You call that music.” pg. 28

Baylor is doing wordplay on Eddie Rabbitt, a country music artist from the 70s-90s. His “I Love a Rainy Night” reached number one in 1981.

“JAKE: He’d put on Lefty Frizell and twirl you around the kitchen until you got so dizzy you had to run into the bathroom and puke.” pg. 50

Lefty Frizell was a country artist in the 50s and 60s.

“LORRAINE: Had a big ‘Frontier Days’ blow-out there. Big to-do.” pg. 85

A June celebration of the wild west.

“LORRAINE: What in the name of Juda’s Priest is the matter with you, boy!” pg. 30

Juda’s Priest is a metal band that was popular in the 1980s.

“LORRAINE: Stop mopin’ around here gettin’ everybody’s dander up.” pg. 52

This phrase means to anger.

“LORRAINE: Baby pictures and 4-H Club pictures and pictures of Jake running with a football.” pg. 67

4-H Club (head, heart, hands, health) is a youth organization for personal growth and life skills.

“LORRAINE: Well, ya’ light one a’ them Blue Diamond stick matches and toss it in there and run.” pg. 88

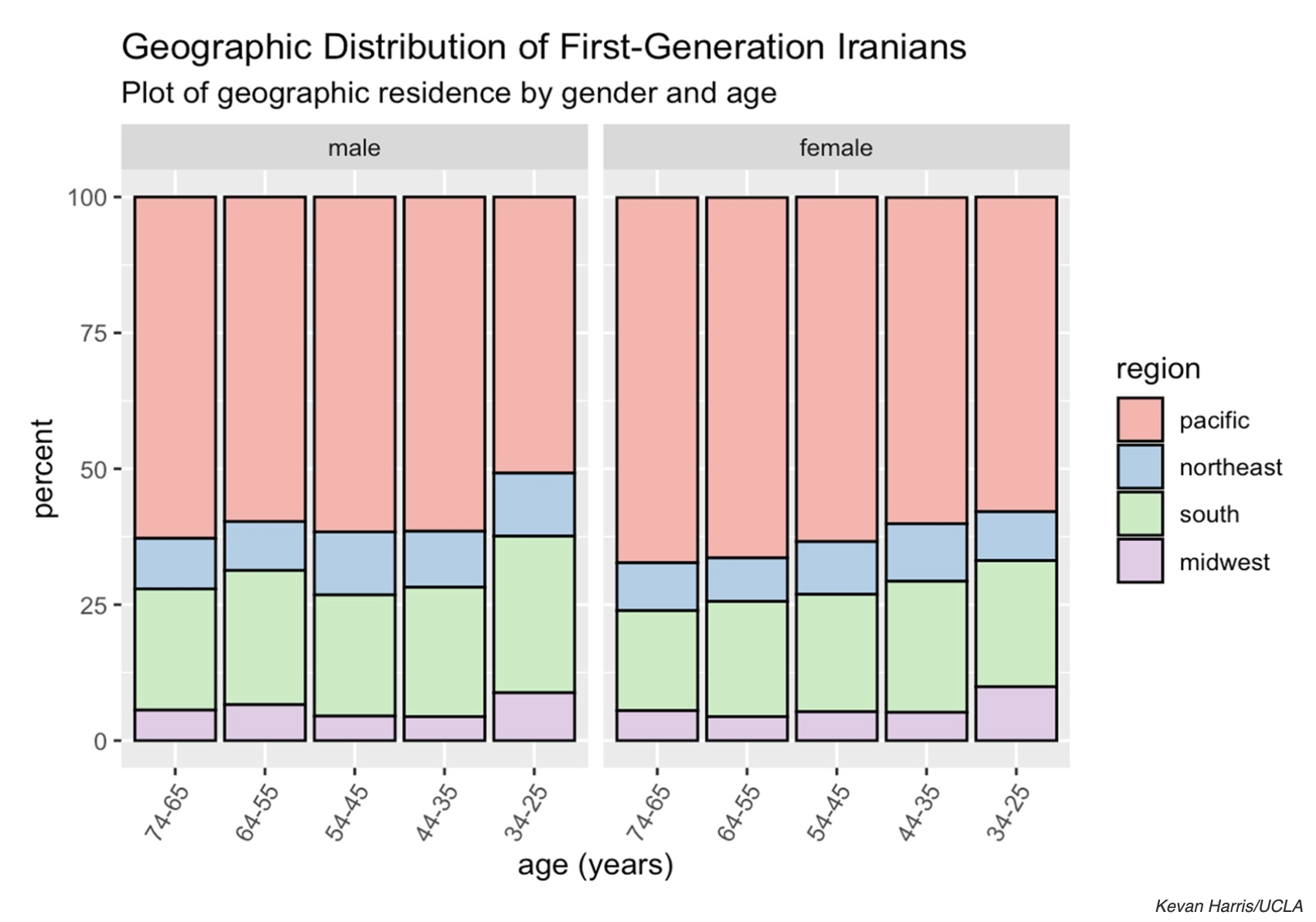

Iranian-American Immigration

First Wave 1950-1979

Second Wave 1979-2001

Third Wave 2001-Present

“Immigrants from Iran began to arrive in the U.S. in the early 20th century, often members of the country’s religious minorities, including Armenian and Assyrian Christians and Jews. In the 1950s, there was an increase in immigration, and in the 1960s and ’70s, an even larger group of younger Iranians and professionals came, often on student or non-resident visas.

But the first major wave of Iranian immigrants arrived in the years immediately preceding and following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which deposed longtime monarch Mohammed Reza Pahlavi and brought Islamist revolutionaries following Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to power. At the time, [Kevan] Harris noted, U.S. immigration law gave precedence to family members of U.S. residents, allowing Iranians already settled in America to bring over spouses, parents and children. Between 1978 and 1980, more than 35,000 Iranians arrived in the U.S.

Since then, there have been spikes in immigration in the late 1990s and early 2010s, with a drop-off during the Trump presidency, according to several sources, Harris said.”

Pre-Revolution Iran

Additional Info

〰️

Additional Info 〰️

Timeline in the Play (Coming soon…)

Azar’s family photos

My grandmother (fashionista)

My dad, my mom, and my mom’s best friend Azar (who I'm named after)

My mom and aunt at my aunt's wedding

My mom’s family at the Caspian Sea

My mom, my aunt and my grandfather sledding

My parent’s wedding, with my dad’s sister and her young son and husband

My grandfather (father's side)

Me and my dad’s sisters in Iran

My dad and his two best friends, in Idaho

Me and my parents at the Coeur d’alene resort in Idaho

My father, his sisters and his mother

My father

My grandmother (mom’s side, same person from the first photo)

Music:

The sound of Shepard

From Shepard’s music notes for A Lie of the Mind:

“In the original New York production, which I directed, I had the good fortune to encounter a bluegrass group called The Red Clay Ramblers, out of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Their musical sensibilities, musicianship, and great repertoire of traditional and original tunes fit the play like a glove. . . . Working intimately with these musicians, structuring bridges between scenes, underscoring certain monologues, and developing musical ‘themes’ to open and close the acts left me no doubt that this play needs music. Live music. Music with an American backbone. . . “

Listen to the original music composed for A Lie of the Mind:

Persian

Collaborative playlist

Montana photography

Take your time taking these photos in:

How do they affect you?

What feeling(s) do they evoke?

When in this play might these images come up for you?

Lake Josephine and Grinnell Glacier, Jim Whilt on horse

Gibbon Canyon and river (and wooden bridge), Yellowstone National Park

Little Chief, Dusty Star, and Fusillade Mountains

Detainees at Fort Missoula: "During World War II, Fort Missoula in Missoula, Montana, was turned over to the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service for use as an Alien Detention Center (ADC) to hold foreign nationals and resident aliens." Japanese, Italian, German, and South American immigrants were detained between 1941 and 1944.

Buffalo at the Moiese Buffalo Preserve

Down the canyon from Inspiration Point

California photography

Disability Theory

Most of the characters in this play are disabled. Beth’s brain injury, Jake’s alcoholism, Frankie’s bullet wound, and the widespread family trauma in this play prominently highlight the topic of disability.

Here is a review of some different models of disability:

The social model of disability argues that societal structures and attitudes– not individuals’ impairments– are the problem that needs solving. Reading A Lie of the Mind through this lens, we may emphasize how the restrictive attitudes of Beth and Jake’s families about their disabilities further inhibit their living truthfully.

Personal accounts:

“Nothing about us without us!”

Alcohol Withdrawal:

While Jake’s illness is never specified in the text, it’s possible that he’s suffering from alcohol withdrawal because he exhibits several symptoms.

Domestic Abuse:

The following questions are from the United Nations to identify domestic abuse. Answer these questions as your character– when do these abusive moments occur in the play? What do they make your character feel and, perhaps more importantly, do?

Attachment Styles:

Anxious (also referred to as Preoccupied)

deep fear of abandonment

Avoidant (also referred to as Dismissive)

avoids dependence

Disorganized (also referred to as Fearful-Avoidant)

vacillates between desire and fear

Secure

comfortable expressing emotions

Alcoholism:

The following is the conclusion from “(Mis)understanding Alcohol Use Disorder: Making the Case For a Public Health First Approach” by James Morris.

“Significant biases and limitations exist in both professional and public understandings regarding the nature of alcohol use and problems. This in turn has important implications for prevention and recovery across structural (e.g., in funding, research and policy), societal (e.g., public attitudes including stigma), and individual levels (e.g., for problem recognition and ‘recovery’). Differences across contemporary professional conceptualizations of AUD [Alcohol Use Disorder] reflect the inherent complexities and challenges of developing accurate and useful AUD ontologies, limitations to current scientific understanding, and historical and socio-cultural influences. These biases and limitations reflect a historically embedded disease-orientated 'alcoholism' paradigm which has been aided by a range of coalescing factors including the worldwide recognition of AA, a biomedical focus on understanding AUD, cognitive biases including reductionism and essentialism, and various societal and commercial motives to construct AUD problems as confined to the biogenetic other. To address these concerns, we advocate for a renewed public-health first approach to alcohol-related harm that focuses on commercial determinants and upstream policies which aim to reduce drinking across the entire distribution of drinkers, continuum models of use and harms, stigma reduction approaches, and further research to support refinement of AUD concepts to facilitate improved prevention and treatment approaches.”

In the context of A Lie of the Mind, this rejection of the disease model of alcoholism highlights the complex difficulties that Shepard’s alcoholic characters go through; a cultural misunderstanding of alcohol abuse creates narratives of blame, shame, and futility that further oppress the individuals effected.

All animal references:

“BETH: Yore the dog. Yore the dog they send.” pg. 11

“FRANKIE: One time you even blamed it on a goat.” pg. 16

“LORRAINE: Used to do this all the time when he didn’t get his own way. Mope around for days like a Cocker Spaniel.” pg. 23

“SALLY: You always called me the Crayfish. You remember?” pg. 23

“BAYLOR: Listen, I got two mules settin’ out there in the parkin’ lot I gotta’ deliver by midnight.” pg. 26

“LORRAINE: You got everybody buffaloed, don’t ya’?” pg. 30

“Before the lights rise, the sound of a dog defending his territory is heard in the distance.” pg. 35

“MEG: How ‘bout these? They’re very kind to the skin. Like having little lambs wrapped around your toes.” pg. 35

“MEG: I used to even put socks on the dogs when they came in.” pg. 35

“BETH: Smells like fish.” pg. 39

“BETH: Iz in there like a turtle? Like a shell?” pg. 40

“MEG: Yes. It’s a grey thing. Kind of like a snail, isn’t it, Mike?” pg. 40

“BAYLOR: I got one day left to bag my limit and this bone-head comes along and scares every damn deer in four counties.” pg. 41

“BAYLOR: Don’t mess that shack up. I spent all afternoon sweepin’ the mouse shit out of it.” pg. 43

“MEG: Well, I don’t understand how a man can be mistaken for a deer. They don’t look anything alike.” pg. 44

“JAKE: What kind of animal… A bear?” pg. 50

“Jake and Sally lock up and stare at each other like two dogs with their hackles up.” pg. 51

“LORRAINE: How can you be so mule-headed stubborn and selfish!” pg. 51

“Mike enters from the porch, covered in snow and carrying the severed hind-quarters of a large buck with the hide still on it.” pg. 60

“MIKE: Then he can feed it to the dog.” pg. 60

“LORRAINE: He’s like a stray dog.” pg. 64

“LORRAINE: Busted open like a road dog.” pg. 65

“SALLY: There was a meanness that started to come outa’ both of them like these hidden snakes.” pg. 69

“SALLY: Like the way that rooster used to do. That rooster we had that went around looking for the tiniest speck of blood on a hen or a chick and then he’d start pecking away at it.” pg. 69

“SALLY: He ran like a wild colt and never once looked back.” pg. 70

“SALLY: I went over and tried to help Dad up but he turned on me and snarled. Just like a dog. Just exactly like a crazy dog.” pg. 70

“BAYLOR: I can’t stalk deer anymore, at my age.” pg. 76

“MEG: I mean what is the big fascination about standing out there in the cold for hours on end waiting for an innocent deer to come along so you can blast a hole through it and freeze your feet off in the process?” pg. 76

“BAYLOR: It’s deer season. You hunt deer in deer season.” pg. 76

“MEG: Like mother used to say… ‘Two opposite animals.’” pg. 77

“MEG: She was like a deer. Her eyes.” pg. 77

“BAYLOR: A deer is a deer and a person in a person.” pg. 77

“MEG: Some people are like deer.” 77

“BAYLOR: I could be up in the wild country huntin’ Antelope. I could be raising a string a’ pack mules back up in there.” pg. 78

“LORRAINE: That was my sorrel mare.” pg. 85

“LORRAINE: He had that big dumb grey gelding you had to throw down on his side every time you went to re-shoe him.” pg. 85

“LORRAINE: One day he just decided he was sick a’ feedin’ livestock and he loaded everything into the. trailer and healed ‘em all off someplace. That was the last I saw of her. Probably wound up in a dog dish.” pg. 86

“Mike walks along, clucking to Jake like a horse and shaking the ‘reins’ now and then.” pg. 88

“BAYLOR: Haven’t you got anything better to do than to monkey around with weapons and flags?” pg. 91

Questions? Contact us.

Looking for your dramaturgs (Martine Kei Green-Rogers and Joan Starkey)?

We can be found via this form or our info on the contact sheet.